Over the last several years, we’ve witnessed dramatic increases in nutritional information. Much of this is related to a new depth of understanding about the role food plays in human health and well-being. This interest is global, as the U.S. is not alone in its concern for the role of diet in chronic illness. Additionally, we now have ever-evolving information on how food choices affect longevity and an optimum level of health well into one’s later years.

The brain-gut connection has become a focus of much of this discussion and is central to scientific investigation. This article summarizes current information with a focus on measures you can take today to boost the health of your gastrointestinal tract. That includes food options that hold promise in boosting gut health and your brain’s wellness.

The human microbiome 101

A microbiome is an ecosystem of microorganisms that live all over the human body — on the skin, in the lungs, in the urinary system, the reproductive system, and in the digestive tract. The number of these organisms is staggering. Cell for cell, we’re about as human as we are microbe!

While caring for the microbiomes on the skin and in the urinary or reproductive systems is very important, in this article, we’ll focus on the incredible system hosted in the gut. The organisms that collectively reside in the digestive tract and intestines especially are referred to as gut microbiota. When balanced, supported, and healthy, the gut environment supports many health-protecting functions. These organisms:

- include viruses, bacteria, fungi, and protozoa

- train and support the work of the human immune system

- help properly break down foods and compounds for use in the body

- modulate the effects of tryptophan metabolism that influence serotonin production, and as much as 95% of serotonin is created in the gut

- can fight to protect us from infection, illness, and weight gain — or make us more likely to fall ill or put on weight

- benefit from the introduction of probiotics, including lactobacillus and other species understood to boost the diversity of the gut microbiota — diversity is key to intestinal health and its effects on brain wellness

Importantly, organisms in the microbiome that typically aren’t harmful can become associated with a disease if their numbers swell. According to 2020 research in Current Nutrition Reports, these issues are more likely in an unhealthy intestinal environment.

Scientific overview of the Brain-Gut Connection

At first glance, the link between your brain with the length of the intestines in your gut is perhaps not so intuitive. However, a quick trip through gut health science and research studies is quite revealing.

“[The] gut microbiota-brain axis refers to a bidirectional information network between the gut microbiota and the brain, which may provide a new way to protect the brain in the near future.”

— Wang and Wang, “Gut-Microbiota-brain Axis”

The connection, or network, between the brain and intestines, goes in both directions. The implications of this understanding point to how inclusively we should be thinking about nutrition and its effects on overall function as well as on blood sugar, weight, and inflammation. There are multiple other effects and outcomes to consider, including:

- The potential for various stressors throughout life to change the gut’s microbiome

- The brain-gut connection is an axis because it involves a network that includes the immune, endocrine, and metabolic systems

- An indication that gut microbiota play a role in immune regulation that affects intestinal health (or disease)

- Increases in age-related changes can result in age-related blood-brain permeability, a factor related to degenerative illness

- The potential role of probiotics in balancing the gut environment by limiting pathogenesis

- The effects of stress, anxiety, and depression on the gastrointestinal tract

“The rates of depression and anxiety are disproportionally high in patients with functional gut disorders.”

— Mörkl, S. et al., “Probiotics and the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: Focus on Psychiatry”

Diet and microbiome health

At the crux of the microbiota-brain-gut axis is the role of diet. It’s worth noting that some gut microbiota-brain axis researchers refer to gut microbiota as “the brain peacekeeper.” That’s a powerful statement to keep in mind as you review food choices that promote gut health. At the same time, the effects on the immune and endocrine systems are associated with the health and/or disease of body systems, including cognitive well-being. Research is validating a growing understanding of the interdependence of these systems with the microbiome — compelling motivation to be mindful of what we put into our bodies.

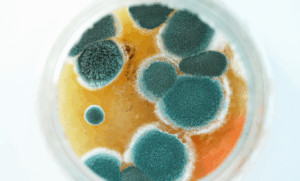

Science about the role of particular foods on gut health continues to expand. There are already clear indicators that the intestinal environment responds quickly to changes for the better. This can happen within a matter of days! A key group that’s part of dietary considerations is the foods that contribute to producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). The gut microbiota generates these metabolite products through food-sourced fiber fermentation.

- SCFAs — butyrate, acetate, and propionate — provide energy for the intestine and contribute to healthy glucose metabolism

- Benefits of SCFAs include improved quality of intestinal mucus production, intestinal health, and fighting inflammation

Take comfort in knowing that an array of tasty foods support healthy gut microbiota.

Foods to improve the gut microbiome

The keyword in thinking about gut health is “fiber!” Its role in fermentation stands as a guidepost for your diet. Some foods are noted to have ‘live’ or ‘active’ cultures, meaning that the bacteria are alive. Foods with live cultures include some yogurt, aged cheeses, kombucha, and kimchi, among others.

Interestingly, other foods contribute to fiber fermentation due to their composition or how they are prepared. Some foods, like tempeh, can be added to a recipe at the end of preparation (an example of a food where live cultures lose their value when overcooked.) Other foods, like cooked rice and white potato, gain value by being cooled before eating. Even reheated, they retain their resistant starch, feed microorganisms, and boost health in the lower intestine. There’s an array of foods that contain resistant starch, including

- Green bananas

- Barley

- Oats

- Legumes, such as beans, peas, and lentils

- Vegetables including asparagus, onions, leafy greens, carrots, sweet potato, and cauliflower

- Fruits with fibers that ferment, such as apples, green bananas, apricots, and raspberries.

Check out our article on how to keep lean mass to learn more about the gut, fiber, resistant starch and how they contribute to weight optimization.

How to eat to support the microbiome

Although your gut will start to adjust to dietary changes within days, it’s wise to take the slow, moderate approach. Your metabolism needs time to adjust. For instance, if you crave a sugary snack, it may be due to insulin resistance and other factors that challenge your ability to make changes.

How much you increase your fiber comfortably will depend on your starting point. It is probably OK to start with swapping out 1-2 low-fiber options with options that have more resistant starch or fiber. For example, switch your rice and potatoes to cooled options with more resistant starch. One week you may add an extra portion of fruit or veg to breakfast. The next week you might add a high-fiber item to your dinner. As always, however, if you have any questions or doubts, consult with a qualified medical doctor or nutritionist.

In fact, a well-informed, sensitive practitioner can guide you through the change process, often ensuring you get optimal results. The support you receive will assist you in selecting foods and supplements that will give your body time to adjust and see the most benefit. Physicians can also document your progress through lab tests that complement your observations, giving you a full picture of your health.

References

Brown, M. J. (2021). How short-chain fatty acids affect health and weight. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/short-chain-fatty-acids-101#TOC_TITLE_HDR_3

Feng, Q., Chen, W., & Wang, Y. (2018). Gut microbiota: An integral moderator in health and disease. Frontiers in Microbiology. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00151 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5826318/

Gao, K., Mu, C., Farzi, A., & Zhu, W.. (2020). Tryptophan metabolism: A link between the gut microbiota and brain. Advances in Nutrition. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmz127 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7231603/

Harvard Health School. (2021). The gut-brain connection. Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/the-gut-brain-connection

Minkoff, D. (2022). What causes cravings for sugar & junk food? Body Health. https://bodyhealth.com/blogs/news/what-causes-cravings-for-sugar-junk-food?utm_source=Klaviyo&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=AS%3A%2010%2F31%2F22%20-%20What%20Causes%20Cravings%20for%20Sugar%20%26%20Junk&utm_content=campaign&_kx=vOaJaq7_GYUTG7OB_ll-wOZ4ZNqSO-wgVyZBrKO1Uq4%3D.PjfDUy

Mörkl, S., Butler, M. I., Hall, A., Cryan, J. F., & Dinan, T. G. (2020). Probiotics and the microbiota-brain-gut axis: Focus on psychiatry. Current Nutrition Reports. doi: 10.1007/s13668-020-00313-5 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7398953/

Nall, R. (2018). Probiotic foods: What to know. Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/323314#probiotic-foods

Silva, Y. P., Bernardi, A., & Frozza, R. L. (2020). The role of short-chain fatty acids from gut microbiota in gut-brain communication. Frontiers in Endocrinology. doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.00025 https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2020.00025/fullWang, H., & Wang, Y. (2016). Gut microbiota-brain axis. Chinese Medical Journal. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.190667https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5040025/